Walter Pentico, (Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency, Courtesy)

LEXINGTON —A Lexington sailor perished on the USS Oklahoma during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. His remains were identified as recently as 2021.

Navy Seaman 2nd Class Walter Ray Pentico, 17 at the time of the attack, was identified by Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency (DPAA) on Feb. 24, 2021.

The six-year Oklahoma Project identified 355 of the 388 crew members who were still unaccounted for when the remains were disinterred from Hawaii’s Punchbowl cemetery in 2015.

The Oklahoma Project, led by anthropologists at the agency’s Offutt Air Force Base laboratory and aided by DNA analysts in Dover, Delaware, resulted in the identification of 361 crew men.

The lab identified all but four of the 23 missing USS Oklahoma sailors from Nebraska and western Iowa.

Pentico was born on March 31, 1924, to parents Sherman and Ethel Pentico in Overton. He had two older brothers, George, born in 1907, and Charles, born 1922. Walter moved with his family to Lexington when he was just two years old.

Pentico attended Lexington Public Schools and was later employed by the City of Lexington. He had been an active member of the Southern Mission Church.

On April 3, 1941, he enlisted with the Civilian Conservation Corps, CCC, at Mitchell.

The CCC was a voluntary public work relief program which had been started in 1933 for unemployed, unmarried men. It was a major part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal program that provided manual labor jobs to those who had lost work during the Great Depression.

Pentico served with the CCC for three months before he fatefully enlisted in the United States Navy on July 7, 1941, only five months before the attack on Pearl Harbor. His two brothers would eventually serve in the United States Army.

As a recruit, Pentico was sent to Denver for physical examinations and then shipped to San Diego, Calif., for seven weeks of training.

Pentico would have undergone the ritual of having his hair sheared off, leaving only and inch on top and bare on the sides.

Assigned to their two-story barracks, Navy recruits were firmly told there were no more floors, stairs, elevators, walls, beds or bathroom anymore, now there were only decks, ladders, hoists, bulkheads, bunks and heads.

Dressed in their dungarees, leggings and white round hats, they drilled and marched for hours on the parade grounds, “under arms, back and forth, up and down, on the oblique, to the rear harch,” wrote author Ian Toll.

After his training was complete, Pentico was assigned to the USS Oklahoma, BB-37. The Oklahoma was the second of two Nevada class battleships, the ship was ordered by the Navy in 1911, and construction began in October 1912.

The Oklahoma was launched in 1914 and mainly conducted fleet exercises in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. The ship was modernized in 1929, which brought her crew complement up to 1,398. In 1936 the ship took part in rescuing American refugees, fleeing the Spanish Civil War.

By the late 1930s, the Oklahoma had been assigned to the Pacific Fleet and made her home berth in Pearl Harbor, along with her other sister battleships.

Pentico had reached the rank of seaman second class by the time he joined the Oklahoma’s crew of over a thousand. He was just 16 years old when Oklahoma left the states bound for Hawaii on Oct. 1.

An ocean away, Japan’s imperial ambitions were growing, despite having been bogged down fighting in China since 1937. By early 1941, the United States put an oil embargo in place, as condemnation for the island nation’s war of aggression in China.

With little resources of their own, Japan was left with two options. Either withdrawal from China and lose face on the international stage or seize the resource rich European colonies of Southeast Asia, which doing so would certainly cause war with the United States.

Ironically, the very man Japan tasked with prosecuting a war against the United States, was one of the most vocal critics of this course of action.

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, then commander of the Combined Fleet, wrote to a colleague in October 1940, “To fight the United States is like fighting the whole world.” He also stated the coming war would be a “calamity,” and was to be avoided at all costs.

Most of the top-ranking officers in Japan’s navy also felt similar, but an insidious trend had been established throughout the country in the 1930s.

Japan’s military did not answer to the civilian government, instead professing their loyalty to their god emperor only. Emperor Hirohito did not exercise a firm hand and thus the military was left to its

own devices, with ultra-right-wing elements pushing for imperial expansion in Asia.

Secretive clans of mid-level military officers, often with a wink and a nod from their superiors, began taking control of Japan’s major domestic and foreign policy choices through intimidation, assassinations and provocation.

Thus, claiming to act in the Emperor’s name, these groups dictated policy and played a part in marching Japan into full scale war against the United States. In the fall of 1941, Hirohito was presented with a unanimous opinion for war with the United States by his Supreme War Council.

With the oil embargo slowly strangling Japan’s economy, the United States beginning a massive naval build-up and their Nazi allies on the move in Europe, the emperor gave the nod for war.

“What a strange position I find myself in,” Yamamoto, the man behind the plan to attack Pearl Harbor, wrote to a friend in 1941, “having been assigned the mission diametrically opposed to my own personal opinion, with no choice but to push full speed in pursuance of that mission. Alas, is that fate?”

Fate or not, Yamamoto came up with a plan which was described as an eleventh-hour revolt against the past thirty years of military planning, according to author Ian Toll.

Japan had envisioned picking off the U.S. fleet as it came across the Pacific to reclaim their lost islands and then using their titanic battleships to crush the Americans in a single, decisive victory.

Yamamoto feared the U.S. Navy would not play their roll and charge headlong across the Pacific early in the fight but would marshal their strength and then unleash it and dominate Japan.

Yamamoto came up with the idea to strike at the American fleet while it was tied up in berth using carrier aircraft with aircraft carriers.

On Nov. 26, 1941, the Kido Butai, “Striking Force,” made up of six aircraft carriers, the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku, left port in Japan, with 408 aircraft, and stayed well north of the commercial shipping lanes, sweeping down on Hawaii from the north.

In Pearl Harbor, Sunday morning was a slower day for most of the sailors who were recuperating from their shore leave Saturday evening, participating in worship services or attending to their duties onboard the ships. Several battleships had their hatches wide open for inspection that morning.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Oklahoma was moored in berth Fox 3 in Battleship Row. She was moored alongside her sister battleships, with Maryland beside her, behind was West Virginia and Tennessee, then the Arizona and last the Nevada.

Pentico would have likely been near his station on the Oklahoma.

The Japanese had achieved complete surprise in their attack, and it has long been debated that Japan had intended to formally declare war on the United States before the attack.

During the Japanese aerial attack, the Oklahoma was struck by at least five torpedoes. After 15 minutes, the ship began to list and capsize.

It’s unclear where Pentico was stationed on the Oklahoma, but at the call to battle stations, many men would have gone below decks and many sought shelter on the third deck, standard protocol during an air attack.

The Oklahoma began to list and capsized within 15 minutes. At 8:10 a.m. she was still upright when two bombs penetrated the USS Arizona and turned the ship into a fireball taking the lives of over a thousand American sailors.

After this strike, Oklahoma rolled upside down. Pentico was one of the 429 men who were killed or missing during the attack.

He had only served on the ship for nine weeks.

While the fate of the Arizona is well known, at the time, the sight of the Oklahoma capsized was even more disturbing to witnesses.

“Three generations of officers and enlisted men had been taught to believe that every battleship was a fortress, permanent and impregnable,” author Ian Toll writes, “For such a ship to roll over like a toy boat in a bathtub seemed ludicrous, almost inconceivable.”

George Waller, a Gunners Mate on the nearby battleship Maryland said, “We had been told all of our lives that you couldn’t sink a battleship, and then to see one go upside down…it was heartbreaking.”

In one of history’s dark ironies, the mastermind of the Pearl Harbor attack predicted what would happen with devastating clarity.

“It is obvious the Japanese American war will become a protracted one,” Yamamoto said, “as long as tides of war are our favor, the United States will never stop fighting…Ultimately we will not be able to contend with the United States.”

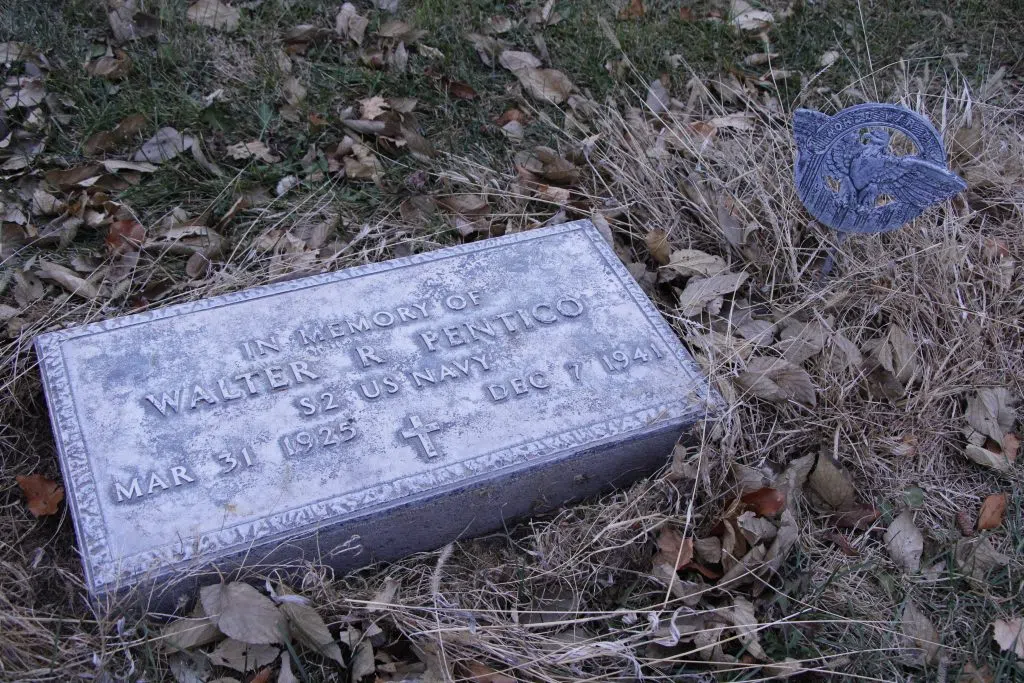

A grave marker for Walter Pentico in Lexington’s Greenwood Cemetery, (Brian Neben, Central Nebraska Today)